Being Good

"Welcome to the land of fuck," says former Detective Kenny Eurell, as a way of introducing viewers to New York City's 75th precinct. During the years he was a police officer, from the late 1970s until the early 1990s, the "Seven Five" in East Brooklyn was the deadliest precinct in the country. An inner-city neighborhood decimated by the crack epidemic, the five square block area was the deadliest precinct in a city that was averaging 3,500 murders per year and countless robberies, rapes, and assaults.

Tiller Russell's documentary The Seven Five (2014) details the exploits of some of this precinct's most notorious officers who took advantage of the violence and chaos of their beat in order to survive and in order to profit. The film opens with officer Michael Dowd being interviewed in September 1993 in front of the Mollen Commission, a panel tasked to investigate police corruption. Dowd's candid reflections on his criminal acts while serving as a policeman in the Seven Five, in those tapes and in front of Russell's camera, are the heartbeat of this documentary.

Dowd testifies in 1993

Disgraced former officer Dowd's voice serves as a Ray Liotta–style entree into life at the notorious precinct, recalling his time as a rookie cop and learning the ropes in an animated fashion, and of becoming a more experienced officer as the seasons roll by: "After about a year, four or five hundred tours of duty, you begin to feel under appreciated, like nobody cares. You're not really stemming the flow of crime like you thought you were gonna. And all of the sudden you see an opportunity come along, and you know . . ." Dowd's persuasive tone explains just how easy it was to make his first "score," and throughout the film during moments where he attempts to display contrition or sober reflection about his crimes—whether it's skimming $400 off a drug dealer at a traffic stop or stealing cash out of a citizen's home—you see the twinkle of mirth in his eye as he recounts yet another out-of-hand adventure with the enthusiasm of a drinking buddy three sheets in.

Dowd fondly recalls his exploits for Russell's cameras in 2014

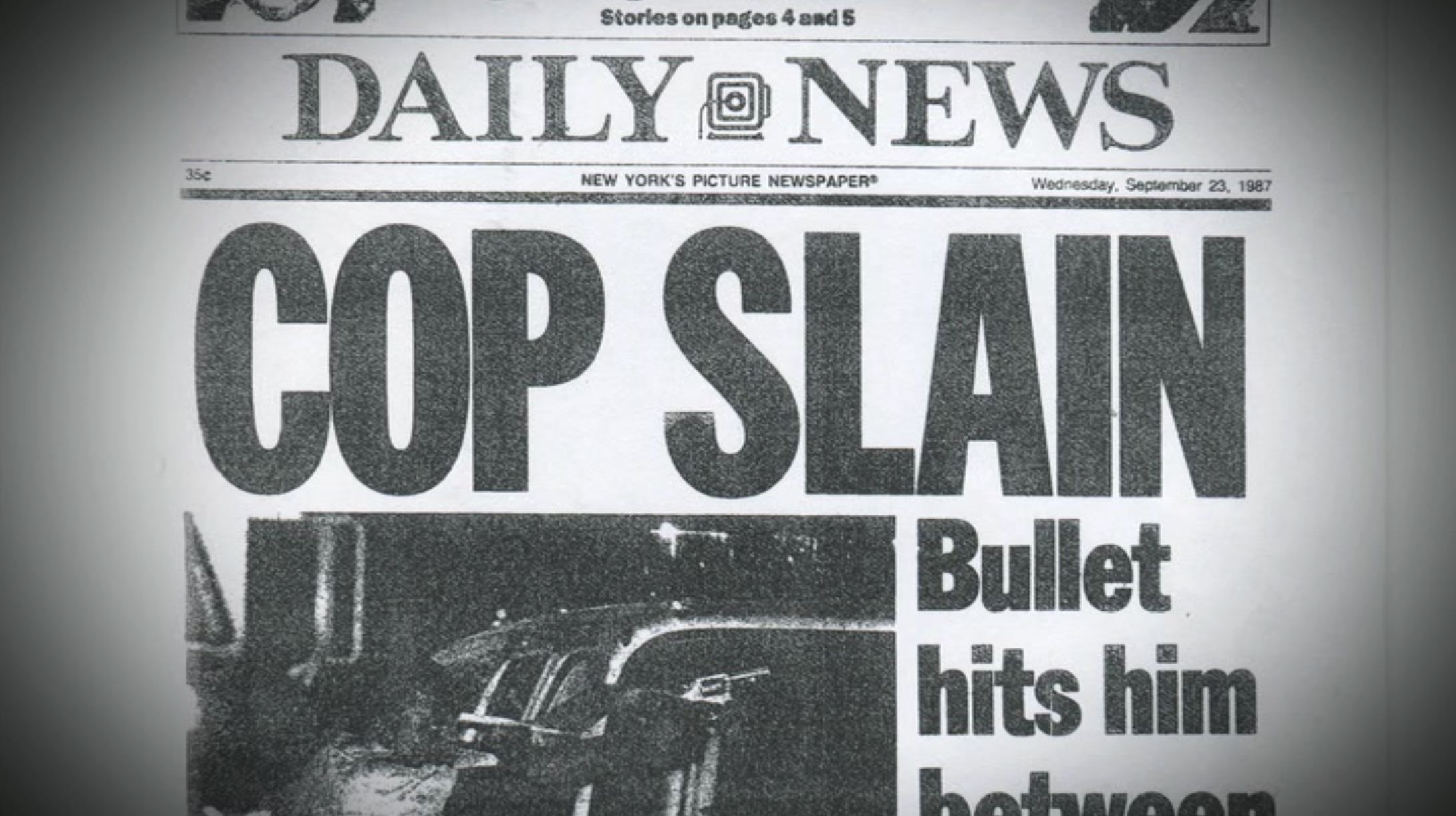

In a segment of his '93 Mollen Commission testimony, Dowd describes to the panel what it means to be a "good" police officer: "Being 'good' means that you would never turn on another cop. If you witnesses something go down, you're 100% behind what that cop does no matter what it is." In 1987, Dowd is given a new partner in the Seven Five, Kenny Eurell. Eurell, a fairly green officer with a wife and two kids, is apprehensive about the match. He's heard the rumors about Dowd's shady activities, but despite his better judgment they make the partnership official and bond in the way that officers in that violent precinct need to in order to stay alive.

Detective Eurell as an NYPD officer (left) and today (right)

Soon the pair are inseparable, and Dowd has ensnared Eurell in enough outside-the-lines adventures that they'd both be considered "dirty" to the eyes of an outsider. Through twenty years of hindsight, Eurell's depiction of how Dowd led him down the path of corruption is carefully hedged with outside blame and disclaimers, minimizing his enthusiasm for Dowd-led capers and maximizing his remorse and doubts about their behavior. But, the facts are that in the late 1980s Dowd and Eurell partnered with the Diaz Organization to provide protection for $8K a week. The Diaz Organization, headed by brash young kingpin Adam Diaz, was a high-level drug trafficking ring that imported kilos of cocaine and heroin to the East Coast from Columbia and onto the streets, netting millions of dollars a year in profits.

Adam Diaz speaks candidly about his reign as drug kingpin in east Brooklyn

Diaz, who is interviewed for the film and recounts his exploits with sinister humor, explains that when he met the pair of officers, "I knew that Kenny didn't have that gangster shit in him. He had that cop look. Mike didn't—he was . . . like me." Smiling broadly, Adam proceeds to detail how once Dowd and Eurell joined his payroll the pair would tip him off about pending investigations and planned arrests of Diaz's crew, protect the deliveries of drugs and cash in transit between drop points, and rob rival drug dealers of their drug stash and cash.

Partnering with Diaz was a major leap from skimming money off of drug dealers to supplement their $600 a week paycheck, and their partnership with Diaz initially didn't sit well with Eurell. "Two months ago I was a regular cop, now I'm a criminal. There's no turning back, there's no becoming a cop again." Eventually, Eurell succumbs to the comforts of the lifestyle that this betrayal of his oath affords, and the officers and their wives begin spending their weekends in Atlantic City and paying for household extras in cash.

Homicide detective Joe Hall (left) and IAD detective Joe Trimboli (right), who independently began to suspect Dowd and Eurell of corruption

The film doesn't let Dowd's enthusiastic rehash of his exploits with Diaz continue on untempered. Intercut with Dowd and Diaz's fond memories of robberies and silenced snitches are interviews with the beleaguered DEA agents and homicide detectives who had been tasked with cleaning up the deadly mess of the drug war. Detective Joe Hall recalls his disgust once he began to suspect that officers within the Seven Five were corrupt and colluding with drug dealers: "Now I have COPS making it possible for this poison to get on the streets?? Destroying people's lives and destroying our neighborhoods?" And despite the film's focus on the exploits of a few individual officers, The Seven Five depicts the corruption within the NYPD as widespread and reaching to the top. Fearing another police scandal, the brass ignored warning signs within their ranks and, in essence, condoned corruption as long as it didn't cause public embarrassment.

More than once during the film Dowd is asked how he got away with a decade+ of criminal behavior while serving as an officer. "There were times I was shocked when I got away with these things," he answers. Everything obviously caught up to everyone at some point, first evinced through watching Dowd's testimony before the '93 Mollen Commission, and hinted at throughout the film with surprising candor by many of the players in this drama. The thrill of The Seven Five is in this array of perspectives—if any of the participants had been missing from the film or still had something to lose by speaking openly, the documentary wouldn't work. But by 2014 everyone involved in this story has paid their debt (criminally at least) and is able to speak for themselves. The film doesn't indict Dowd and Eurell for their exploits, instead allowing us to choose whether to condemn or exonerate the disgraced officers with their own words and (lack) of remorse.

The Seven Five is available for free streaming on Netflix (with membership) and is also available on DVD. Subscribe to be notified when a new essay is posted ~