Don't Fear the Reaper

“The pressure’s on.” That’s how Cooper describes the situation to his girlfriend, Sarah, in The Nickel Ride (1974). He’s a cog in the underworld, a mid-level operator who’s certainly not a grunt but who takes orders from a few layers of boss.

Cooper’s the Key Man, the guy who controls all the space: warehouses in LA’s Skid Row where mob outfits from the Midwest store their ill-gotten loot until it can be sold or shipped back east. Although he works for the mafia Cooper isn’t a thug or an outlaw type—he wears a button-down shirt and jacket to work and keeps an office. Right now he’s in the midst of a big deal securing The Block, a 400,000 square foot city block of beautiful emptiness that will soon be all his.

(left) Jason Miller plays Cooper (right) The Block

There’s a few problems with the final details—the local cops, the teamsters, nothing he can’t handle. But more than that, things just seem off lately. Whenever Cooper tries to make a deal his authority is questioned, people don’t seem to think he has the juice or the muscle to back up his promises anymore. The higher-ups aren’t returning his phone calls, underlings are starting to talk back to him. “There’s some talk going around,” is all anyone will admit when Cooper asks squarely what’s going on, even though his boss, Carl, assures him everything’s fine and the deal’s as good as done.

Is someone out to get him, or is he just being paranoid? Is he losing his grip?

Actor (and Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright) Jason Miller is perfectly dull and compact as Cooper, whom he portrays with an inward slouch that’s ready to pounce at the slightest hint of danger. And right now Cooper is a man on his guard—until The Block is secure his safety with the organization is in jeopardy, and in his line of work the only retirement package comes in a pine box. Miller provides just the right amount of gravitas and mystery to convey how this unassuming businessman type has survived so long in such a cutthroat business.

And it is a business. Although many films have recounted stories about renegade 1930s-style outlaws being penned in by increasingly bureaucratic organized crime outfits, Cooper and his boss Carl (John Hillerman) are a generation past that. They came into this outfit when it was already a well-oiled machine, and their personalities allowed for fitting themselves into this assembly line structure that dilutes personal character and integrity while prioritizing fast results at any price.

Cooper with boss Carl (John Hillerman)

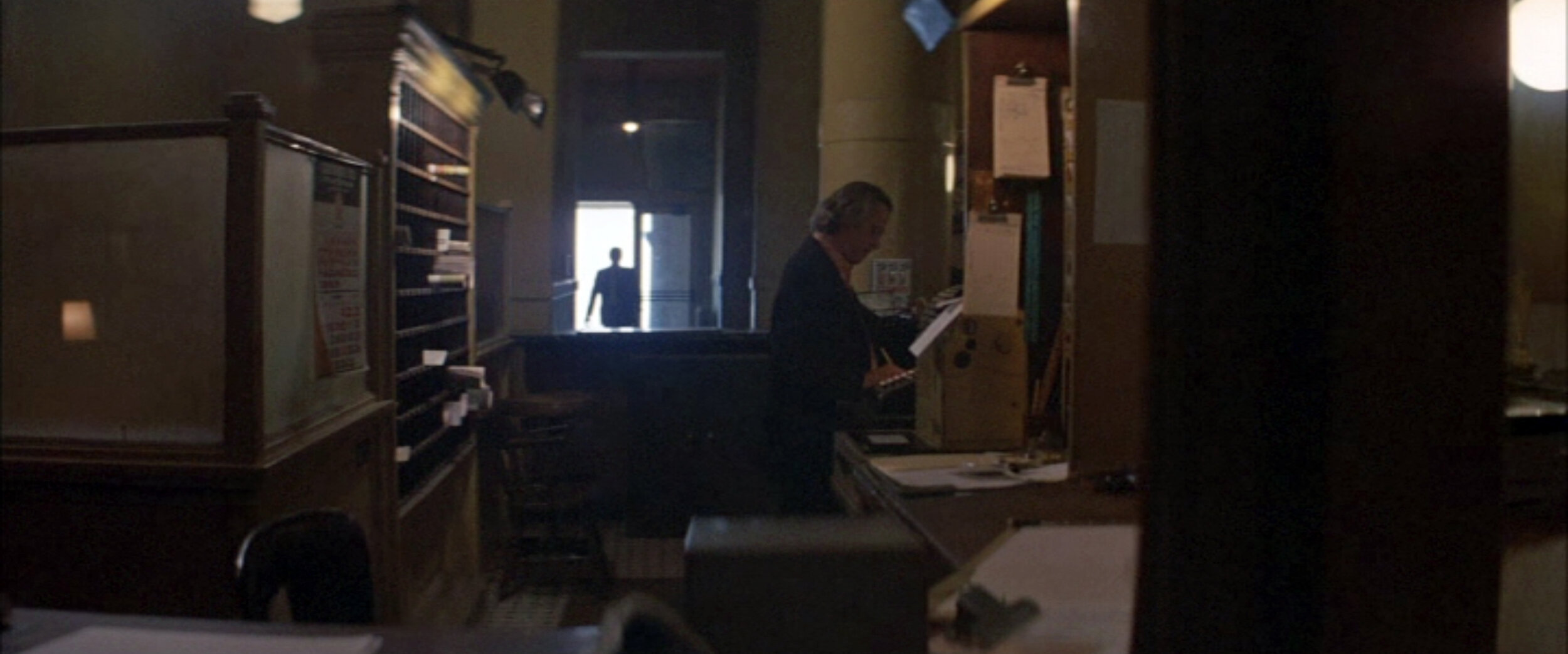

These men live in the monochromatic browns, greys, and tans of smog-filled downtown Los Angeles, where it’s impossible to distinguish between open businesses and buildings slated for demolition. Everyone looks and sounds like they’re from back east, and they bring with them a seasonal gloom and a monotone efficiency that is impenetrable even during the long sunbaked afternoons or a surprise birthday party. They soak up their California rays through the dusty slats of venetian blinds in the poolhalls, barrooms, and opulent lobbies that harken back to an era of prosperity long past.

The smoggy, nocturnal Los Angeles of The Nickel Ride courtesy of cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, who shot Blade Runner (1982) as well as Sleeping All Day favorites Cutter’s Way (1981) and Play It As It Lays (1972)

The last thing Cooper needs comes in the form of lanky, yakking, cowboy thug Turner, imported from Oklahoma. Installed by Carl to learn the lay of the land while the heat cools off back home, Cooper is tasked with keeping an eye on this new recruit. While Cooper ekes out the minimum number of phrases to get his point across and appear mildly social, Turner is a pinball machine of chatter, delighted to be in the midst of big city action and eager to please his new mentor.

Bo Hopkins is Turner

Turner is played by Bo Hopkins, an actor who channels all of his trademark kinetic energy and mercurial charm into a character who matches Cooper’s staid cream shirt and dark suit with a red rhinestone-studded T-shirt, cowboy boots, bellbottoms, and a jean jacket with a giant pot leaf patch emblazoned on the back. Turner is at home wherever he is, while Cooper seems uncomfortable even while he’s asleep. Cooper winces at Turner’s psychedelic good cheer, even though the young upstart professes an admiration for the Key Man and seems eager to help with everything from chauffeuring to violence.

What the hell is Turner out here to do exactly? Boss Carl didn’t elaborate, and whenever Cooper questions Turner directly he gets a sideways phrase of Southern politeness with a menacing smile. Although this brief description on paper (or screen) sounds like the makings for a great buddy-cop/gangster scenario, director Robert Mulligan keeps the interactions between the two tense and off-kilter. In Cooper’s line of work it’s equally likely that Turner is here to kill him, take over The Block, or help him twist the arms of the last remaining kinks in the deal. Hopkins snaps off Turner’s charm with just enough precision to display a ruthless core beneath the cowboy’s supposedly harmless veneer, and Miller’s somnambulant Cooper never so much as cracks a smile at any of the cowboy’s jokes.

The vagueness and strangeness of the film’s plot is not a hinderance but instead the very element that makes it so compelling. A grinning cowboy gangster and potential hitman gunning for a middle-management mafia functionary over empty warehouse space? The Nickel Ride relies on everything we’ve watched before to fill in the details absent from the action. The words “mob,” “mafia,” or even “organization” are never spoken, with the outfit that Cooper, Carl, and Turner belonging to referred to only as “they” or “our people.” This careful vocabulary isn’t derived from pragmatic caution regarding surveillance or wiretapping but based on a deeper sense of paranoia and omniscient threat that first Cooper, then the audience, starts to feel in the pit of their stomach.

If Chinatown, released seven months before The Nickel Ride in the summer of 1974, was the first signature neo-noir, then this film is classic noir’s death rattle, an acid flashback–style nightmare that’s so strange yet so familiar, to the point where even the hero knows how the story is going to end.

A washed-out and cropped print of The Nickel Ride is available on YouTube here; Shout! Factory has released a crisp remastered version on DVD that’s available here. Subscribe to Sleeping All Day

Cadillac Cowboy, a print honoring Bo Hopkins, is available on my portfolio site