Within the Law

All J.J. Johnson ever wanted to be was a cop. He knew things weren’t going to be easy as the first African American in the county sheriff’s department, but he was willing to put up with a little ignorant nonsense in order to protect and serve.

But the bullshit started immediately. He gets hassled by another officer in the parking lot his first day on the job, his partner scrutinizes his behavior during a routine traffic stop, and his commanding officer is on his case 24/7, writing him up for every little infraction or misstep. Are the guys being hard on him because he’s a rookie, or because he’s Black?

This is one of the issues posited in Charles Burnett’s The Glass Shield (1994)—the sneaky, insidious way that bias manifests itself in the police department (and in any workplace for that matter). J.J. (Michael Boatman) develops an uneasy alliance with the only other outsider in the squad, Fields (Lori Petty). Being Jewish and female, Fields has two strikes against her in the old boys’ network. At first, both deputies try to avoid becoming the main outcast in the department at the expense of the other, with Fields always emphasizing J.J.’s junior rank by calling him “trooper” and J.J. nagging Fields with deliberately insensitive remarks like “I thought this was supposed to be a man’s job.”

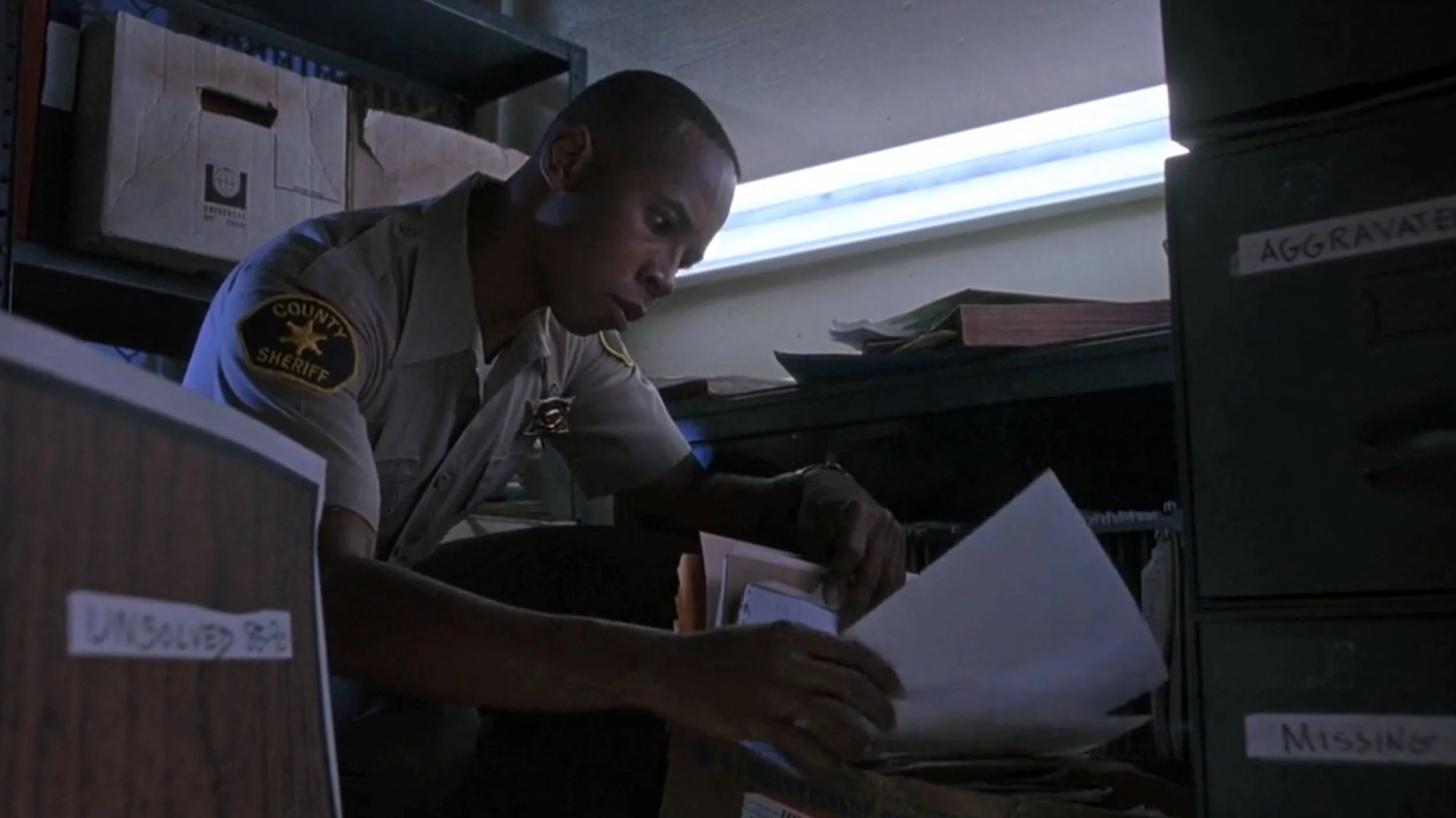

As J.J. gets the hang of things he feels more at ease with the others and himself in the role of cop. “Remember,” a fellow deputy snaps at him during roll call, “you’re one of us now, not a brother.” This tacit implication is that J.J. is now more blue than anything else, and his loyalty to his new family is tested almost immediately.

During a “routine” traffic stop where his partner pulls over African American driver Teddy Woods (Ice Cube) and his car is searched with no probable cause, J.J. turns up a 9mm gun. A 9mm was recently used in an unsolved robbery-homicide, and Woods’s rap sheet and complexion make him as good a suspect as any. The case proceeds to trial and J.J. is called up to testify and corroborate his partner’s doctored version of events. J.J. is torn—if he tells the truth, the case is thrown out and Woods walks. And he’s guilty as hell, right?

As soon as J.J. backs up his partner’s lie on the stand, he’s confronted with evidence that there’s more going on than a simple probable cause workaround. As the trial progresses, inconsistencies crop up in witness statements and ballistics can’t match the gun used in the homicide with the one confiscated from Woods. Plus, the detectives in charge of the investigation are rotten (and we know they’re rotten because they’re played by hatchet-faced heavies Michael Ironside and M. Emmet Walsh). But are the detectives and prosecutors trying to railroad Woods because of his race, their own incompetence at solving the murder, or something more intricate and sinister?

Needing to bounce his suspicions off a sympathetic ear, J.J. naturally turns to Fields, the only other person in the department who knows how the game is played but has the objectivity to see how the corrupt machine works. Fields isn’t at all surprised that an innocent man is on his way to serving a life sentence, but she’s too jaded and burnt out from the years of abuse on the force to stick her neck out for what she perceives is a battle already lost.

What begins as a thoughtful mediation on racism and sexism in the police force veers at this point into a noir-tinged thriller, as J.J. finds himself quickly embroiled in a cover-up scandal that reaches back into the “bad old days” of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s department. By funneling the plot into a closed-circuit conspiracy yarn (loosely based on real incidents in the Signal Hill municipality within LA’s Long Beach division in the early 1980s), the department’s pervasive racist and sexist attitudes become secondary elements of the story. J.J. and Fields may have been initially singled out because of who they are, but they’re now being targeted because of what they’ve uncovered.

“Thriller” is a term to be applied very loosely, as from start to finish The Glass Shield is a slow, meditative look at the genre that tracks more like an arthouse film than a police procedural or an indie shoot ’em up. Its stylized and isolated feel uses LA County as a substitute for Anywhere USA, and in doing so the film avoids a dated feel that bogs down other police films of that era. The film most closely resembles the reenactment scenes from Thin Blue Line (1988) that, aside from the odd DOS computer screen, still resonate as contemporary—a realization which in itself emphasizes the sadly enduring problems of inequality that pervade law enforcement twenty-five years later.

What the film’s bloodless, matter-of-fact tone does best is display how casually the law enforcement machine dehumanizes minorities and the poor. We see an arraignment hearing of primarily white attorneys presiding over the futures of Black and Brown defendants with the boredom of postal carriers sorting mail, doling out jail sentences in the years for minor offenses and later apologizing for miscarriages of justice with all the passion of someone running late to a lunch appointment.

The police in The Glass Shield are isolated from the community. They live in a closed-off world that feeds on fear and ego in order to sustain itself, a fish tank of suspicion and mistrust where officers are told to protect and serve; the questions of “who?” and “at what cost?” are of no consequence. We see deputies Johnson and Fields alone in a frame together, pitted against a white cop chorus that’s a mustachioed sea of hostility, whose only concern is allegiance to the department even if it means undermining the very tenets of the institution they’ve sworn to uphold.

The Glass Shield is available for rent online via Amazon, YouTube, Google Play, and Vudu. Subscribe to Sleeping All Day