California Soul

Spoiler alert: there is no laughter in The Laughing Policeman (1973). Or even much smiling.

The film begins with a thrilling edge-of-your-seat action sequence: a man is pursued in the night by several armed and shifty-looking characters though the streets of San Francisco. He boards a Chinatown-bound bus, presuming safety amongst a well-lit group of strangers. As the bus approaches Portsmouth Square park, the pursuing hoods open fire with assault rifles and slaughter everyone on the bus, including our man in question and a half-dozen “bysitters.”

Lurching to the scene of this grizzly pre-dawn slaughter is Detective Jake Martin, played by Walter Matthau. Matthau uses every inch of his rubbery, blasé charm in casually tabulating the victims, tracing the pattern of execution and calling out personal details of the dead for possible clues. His morning quickly gets much worse: one of the victims on the bus is his partner on the homicide squad, Jake Evans.

Martin (Matthau) discovers his partner at the crime scene

Martin now has to figure out what the hell Evans was doing on that bus, and if any of the cases he and Evans were working together had anything to do with this bloodbath. Bruce Dern plays Larsen, another member of homicide who gets partnered up with Martin for the duration of the investigation. Larsen is everything wrong about the “bad old days” of law enforcement: he’s racist, sexist, hostile, vain, violent, and a really shitty investigator. Martin and Larsen are ordered to wrap up this quick and find a suspect—any suspect will do—in order to take the heat off the department and quell the public’s fears about a repeat performance. As the days spread into weeks and Martin insists that this “bus murder” investigation ties into an old case of his that Evans was fascinated by, Larsen complains that this level of detective work gives him a headache: “Oh man, I’m used to busting street people.”

Larsen (Dern) and Martin are going in circles trying to solve the “bus murders”

What starts off as a bang-up thriller laden with San Francisco locations devolves into a bizarrely meandering who-cares-whodunit. Director Stuart Rosenberg is much more adept at capturing the color of the city than the urgency of the plot. San Francisco’s local freaks, characters, and crazies get ample screen time, often at the sacrifice of plot or character development of the main players. As this kaleidoscope of humanity shows, the summer of love ebullience bred in the city just five years earlier has long since worn off, soured after years of community indifference, too many cops like Larsen, and the never-ending Vietnam War. The mood in the squad and on the streets is sharp and bitter.

Although he’s convinced that his instincts about this case are right on, Martin, like the audience, is dismayed by their lack of progress. He admits the police’s inherent shortcomings to Larsen, “Cases never get broken through real investigations, it’s always when someone rats on someone else.” In the midst of scenes that don’t quite fit together, The Laughing Policeman manages to illustrate a point many cop films overlook—that a case of real substance and complexity like this one (and the ones that populate most procedurals) is so rare that most investigators don’t know how to handle it when it does come along.

The crime scene circus

The film is a remarkably faithful adaptation of the Swedish source novel of the same name, penned by Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall in 1968. Aside from the locale shift, the most striking difference of the film adaptation is how the murder itself is viewed. In the novel, the Swedish police discuss at length that part of the challenge of solving a crime like this is that in Stockholm there is no national precedent for such an unspeakable act of brutality. They go on to remark, ironically, that one has to turn to the United States to glean insight into these savage crimes: “Unlike us, the American psychologists have no lack of material to work on . . . the Boston strangler, Speck, Whitman, Unruh . . . Mass murders seem to be an American specialty. Plausible theories to why it is so? The glorification of violence. The career-centered society. The sale of firearms by mail order. The ruthless war in Vietnam.” This admired “wealth of knowledge” found within the US is a liability for our detectives when the action is moved stateside: since these shootings have now become so common by the early 1970s, the number of possible suspects and motives is overwhelming. “Gotta be a hardcore crazy,” dismisses Larsen, but in 1973 San Francisco that casts a pretty wide net. What this film depicts is the first season in which mass murder was accepted as just another urban hazard, when the trees were just blooming on an era that we’re still in the midst of.

San Francisco freak-out: Hippies, narcs, pimps, Krishnas, hustlers, Hell’s Angels, and transgendered folk

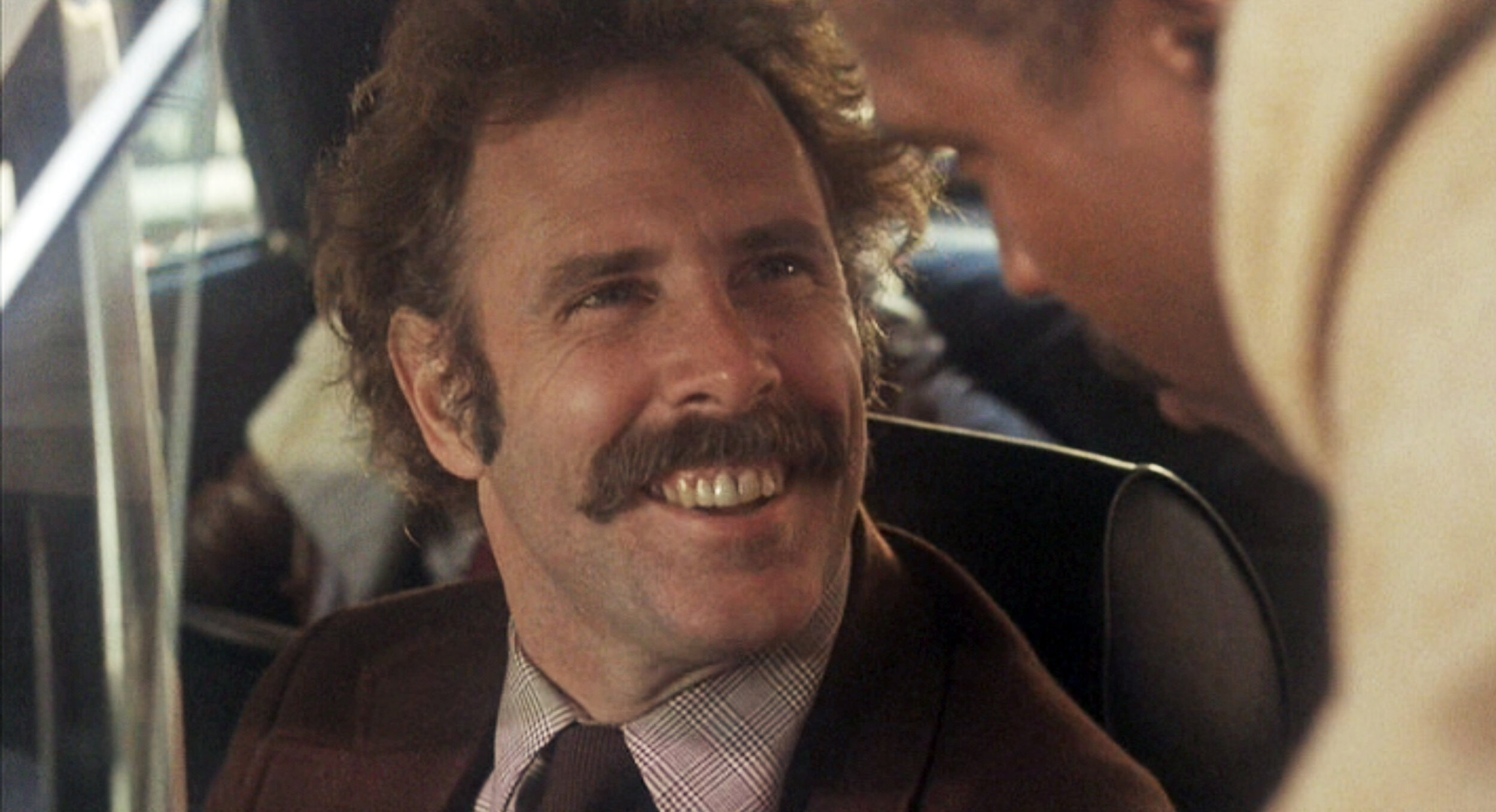

Matthau and Dern are an odd pair that never quite gel, which is to their credit as actors. Their characters represent divergent sides of law enforcement in a changing era—Matthau as the resigned and with-it cop with a “live and let live” attitude, and Dern as the new generation of headcracker who joined the force in order to maliciously command respect behind the safety of a badge. For two actors so adept at comedic character roles they rarely allow their humor to shine through, but when they do it’s in wafer-thin, deadpan slices.

Dern’s smarmy Larsen and Matthau’s brooding Martin

As a police procedural, The Laughing Policeman is a woeful failure. As was unfortunately a pattern for most of director Rosenberg’s films (with the notable exception of Cool Hand Luke [1967]), by the third act the film’s tension has fizzled into anecdote, and the plot becomes so convoluted you stop caring. The big reveal at the end is treated as an afterthought. That being said, the movie is still an important link in the San Francisco cop chain alongside Bullitt (1968) and the Dirty Harry films (1971-88). Matthau’s perma-rumpled Martin has an emotional register just higher than McQueen’s somnambulant Bullitt, and well below the gnashing zeal of Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callahan. For Callahan, keeping the streets clean of scumbags is a personal holy war; for Jake Martin, it’s a fruitless effort that only causes heartburn.

The reason to watch The Laughing Policemen is to revel in the film’s real main character, 1973 San Francisco. The film depicts like no other the wild folks and different neighborhood attitudes found in a city on the brink of immense change (albeit in an amplified version). We see what our season of now looked like when it first began, when mainstream acceptance of mass murder was a just-swallowed pill and you could still find hippies on Haight Street.

The Laughing Policeman is available on Blu-ray from KL Studio Classics. Subscribe to Sleeping All Day