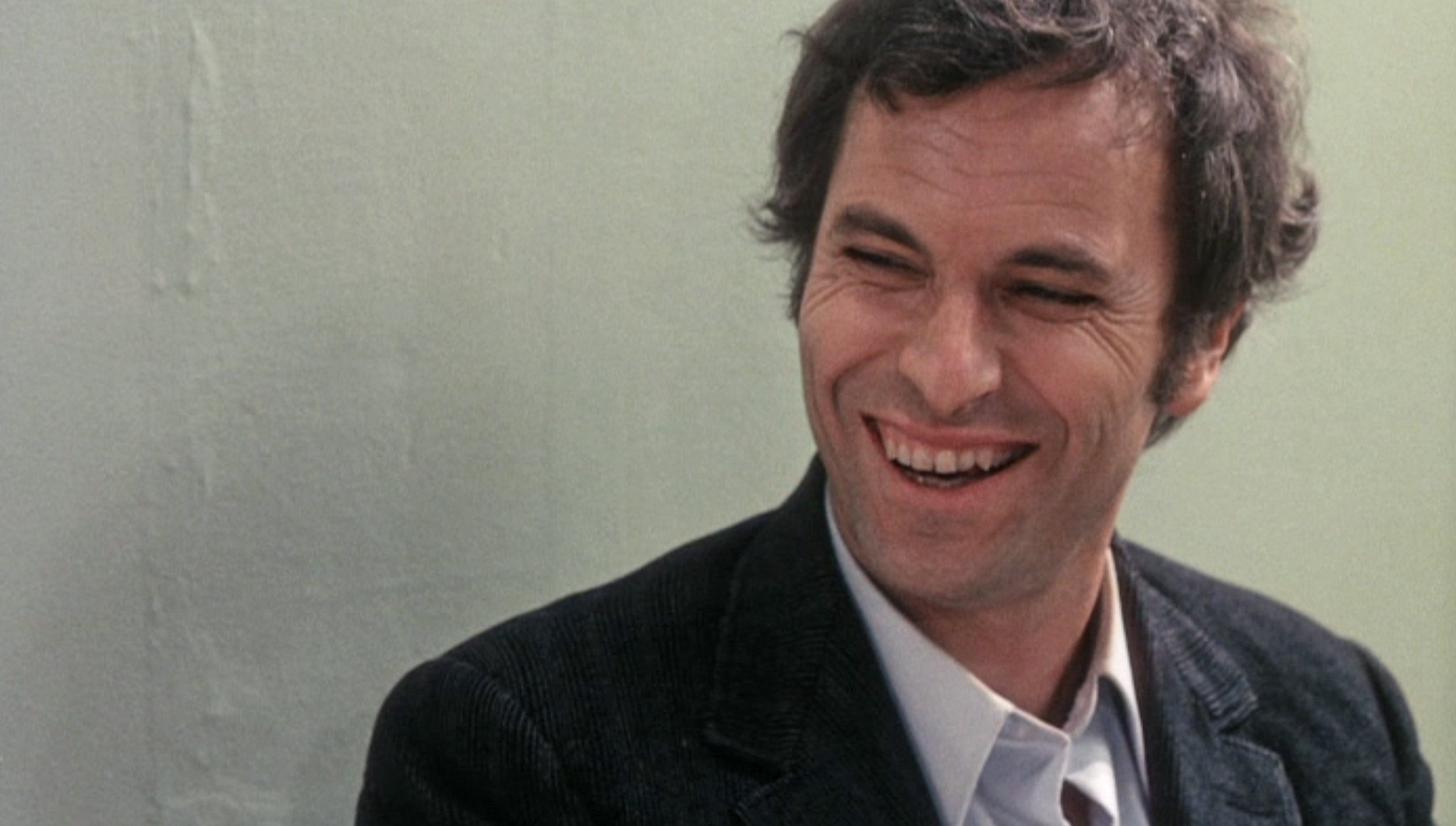

Beautiful Loser: The Adventures of Rip Torn

Rip Torn could do it all: Broadway, TV thrillers, indies, Hollywood war epics. Hailing from Temple, Texas, the actor brought a Southern warmth and charm to even his most villainous roles, with a 1,000-watt smile that stole every scene he appeared in. He was destined for fame, the kind that never really materialized—but for a few years in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it seemed as though he was well on his way.

Torn came up in the New York theater circuit in the early 1960s, earning rave reviews and a Tony nomination for his performance in Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth. His first on-screen credits were small-screen ones: starring roles in episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Route 66, and Thriller. He clawed his way into films, often as the Southern-flavored heavy, reprising his role in Sweet Bird of Youth (1962, costarring alongside his then-wife, Geraldine Page) and appearing as the bitter gambler Slade opposite Steve McQueen and Edward G. Robinson in The Cincinnati Kid (1965). In an early blink-and-you’ll-miss-him appearance in A Face in the Crowd (1957), he is touted as the perfect replacement for Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith), a TV folk hero pursuing celebrity power and nationalist political ambitions. In sticking to the East, Torn and Page eschewed the opportunity to fold themselves into the Hollywood machine, and as a result Torn starred in a number of offbeat independent productions.

One of the best films of this rich period is Payday (1973). Torn stars as Maury Dann, an up-and-coming outlaw country star. He’s still playing roadhouses and one-nighters, but he’s traveling with a caravan of handlers and scooping up groupies regularly. There’s a lot riding on Dann’s career: he’s now got a staff to support, not to mention an ex-wife and two kids. When the film opens, the troupe are on their way to Nashville. They’re scheduled to take a few weeks off from touring to cut a new album and appear on the Buck Owens Show and the Johnny Cash Special, not to mention a performance at the Grand Ole Opry.

Left: Getting paid after a gig (with Michael C. Gwynne); Right: lining up a post-show liaison (with Linda Spatz)

But Dann is restless and anxious to stay on the road, where the money is: “I don’t want to hang around Nashville waiting for Johnny Cash!” he growls. The same thing that drove Dann forward all those years, fighting his way up the charts, is now pushing him to a new edge, one that his friends and managers find alarming. He’s up late jamming with the band and carousing after shows, then back on the highway at dawn headed for the next gig. Pills to wake up, booze to go to sleep. Something’s got to give.

A story of an out-of-control musician can often veer into the realm of formulaic tedium, and Payday is very careful never to play to expectations. Dann is neither a sociopathic sinner nor an oversensitive genius. He drives his team only as hard as he drives himself. Early on in the film he detours off the highway to visit his mother, a withered old woman looped from years of little helpers and wholly dependent upon her son’s financial support. Torn conveys the weight of the situation literally—dragging himself though her house, tidying up and losing his temper at the things that aren’t being kept in better order by the people he’s paying to do so. There’s a growing sense of frustration and irritability caused by the increased responsibility Dann’s been shouldering as his fame has grown, with everyone around him wanting more of his money, more of his time, and more of his celebrity for themselves.

Left to right: Dann visiting his dependent mother (Clara Dunn); disappointing his ex-wife (Eleanor Fell); listening to the song of a young hopeful

Despite these burdens, Dann is far from a gloomy character. To keep things balanced, he steers hard into moments of fun to keep himself and everyone around him amused. He diffuses both depression and tenderness with a grin and a joke, encouraging folks to stop mulling over the future and get back to enjoying the moment. While Dann may occasionally do dastardly things—like have an intimate moment with a groupie (Elayne Heilveil) while his main lady, Mayleen (Ahna Capri), is sleeping right there in the back seat of their sedan, or shoot a pistol into the air from their moving car—it’s Torn doing them, so we’re with him. At any moment he can cut the nonsense and put on a solemn face when signing an autograph for a traffic cop to beat a speeding ticket or meeting with an influential local disc jockey. Dann may be a bastard, but he’s not an asshole, and it’s an important distinction. His ego is based on a solid foundation of hard work, night after night, and he acknowledges and respects the fans who’re responsible for his current good fortune (or at least, he knows enough to pay lip service to them). Just as much time is spent with Dann as he sits by himself composing a new song as when he gets into a shouting match with Mayleen by the side of the highway. By taking the time to show that it’s both the quiet moments as well as the loud ones that go into making a star, Payday relies heavily on Torn to carry the full range of one man’s emotions, and the result is a film that’s unforgettable and damned enjoyable.

Top right: Ahna Capri plays Dann’s main girl, Mayleen

A film version of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer (1934) seems at first a bit of a ridiculous proposition. How could one man’s internal monologue, often X-rated and full of rambling asides, be depicted on film? In 1970, independent producer-director Joseph Strick decided to retain the monologues and cast Rip Torn as Miller to deliver them. With no budget to speak of, out are any period trappings of 1930s Paris, or any attempts to fashion Torn into a visual counterpart of the author. By hacking away at the book’s window dressing, what’s left is the essence of Miller’s work—the joy of life, courtesy of Torn’s 1,000-watt smile. He convincingly drops his Southern accent in favor of a curly Brooklyn snarl, which unfurls like a red carpet when sizing up a free dinner invitation and snaps like a window shade during an argument with his wife, June (Ellen Burstyn). Repositioned in a 1970s-ish Paris, many of the sexual escapades of the novel, as conducted by Miller and his middle-aged friends, seem downright stodgy. Monologues by Torn are draped over shots of street-life Paris to give things a semblance of plot, but like the novel, the film is essentially a series of scenes tripping through several months in the life of a down-and-out writer scrounging his way through the intelligentsia and seedy bars and brothels of the City of Light.

The film’s depiction of women is exploitative and one-dimensional; they’re all either manipulative shrews or teases or prostitutes. But while there’s plenty of sex and foul language, it’s not entirely an exploitation feature. There’s something great about Tropic of Cancer that has nothing to do with any of this, which rests in the moments between those scenes, when Torn’s Miller is by himself, cackling into the night after sneaking out on a dull teaching gig or sticking his head out the sunroof of a taxi to watch the Seine rushing by. It’s the joy of experience itself—the thrill of being alive on one’s own terms—that Strickland’s Tropic of Cancer captures better than other films made from Miller’s work.

Left: Ellen Burstyn plays Miller’s wife, June; Right: Girl-watching in Paris

Coming Apart is nothing like Payday or Tropic of Cancer. Released before either, in 1969, it’s a black-and-white experimental film journal of sorts, documenting the day-to-day activities of a psychiatrist camped out in a high-rise condo in Manhattan. Torn plays Joe Glaser, the doctor “coming apart.” He’s taken a leave of absence from patients and installed a hidden camera in the living room of the apartment he’s holed up in. The film consists of the moments Joe turns the camera on, primarily to record his sexual escapades with women. This may sound tedious and even more exploitative than Tropic of Cancer, but it’s not. The longer these haphazard scenes—which often begin or end mid-sentence—play out and stitch together, we see a man in deep distress: about his separation from his wife, his rejection by a former lover (the phenomenal Viveca Lindfors), and his inability to develop any foundation of self-respect that will allow him to move on with life alone.

The artifice of the film’s construction, though unique and compelling, makes it feel today like a dated curio from late-1960s New York—more a record of a time and place than a bona fide feature film. But it’s not for lack of trying on Torn’s part. In his seduction or genuine attempts at intimacy with a dozen or so women, he becomes a floor show of moods, from the charming doctor to the shy intellectual to a wounded, feral animal. We can’t gauge from one scene to the next what face he’ll display to his wife, his new lover, or a sidewalk pickup. The longer we watch, we begin to spot the cracks in the various masks, as when humor sneaks into an intense scene between him and a former patient, or when a spot of moodiness clouds an otherwise idyllic sexcapade. Joe can’t get a handle on who he wants to be with these women, or who he is without them. If his Henry Miller is wholly at home with his flaws and embraces them, even celebrates them, and Payday’s Maury Dann is resigned to his shortcomings, Coming Apart’s Joe Glaser is drowning in them, refusing to move forward with his career or give up recording these encounters until something smashes open, even if that ends up being his sanity.

Top left: With Sally Kirkland. Top right: With Viveca Lindfors

So what the hell happened to Torn? Why did he not become as legendary as other, arguably less talented, actors of the day? An outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War, he often equated his radical activism in the 1960s and 1970s with the dearth of good film opportunities. His daughter, Angelica, offered a less noble reason: a lifetime of alcoholism. Torn’s biography is littered with DUI arrests, beginning in the 1970s and continuing into the last decade of his life. “He’s pissed away so much—so much of his time and so much of his talent,” said Angelica in a sensational feature on Torn’s 2010 drunk-driving arrest in the New York Post.

Torn continued to work in theater on and off Broadway, and steadily in supporting film roles, until the late 2000s. He earned a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination for the feel-good biopic about Marjorie Rawlings, Cross Creek (1983). He was David Bowie’s earthly foil in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), Albert Brooks’s heavenly counselor in Defending Your Life (1991), and Zed, the shadowy boss overseeing extraterrestrial law enforcement, in Men in Black (1997; he also appeared in the 2002 sequel). He was nominated for an Emmy six times for his role as Artie in The Larry Sanders Show, finally winning in 1996.

It’s a shame that Rip Torn never became a big star, because after watching him in Payday, Tropic of Cancer, and Coming Apart, we see how the loss is just as much ours as his.

Payday is available to watch for free here. Tropic of Cancer is available streaming via Amazon, YouTube, and AppleTV. Coming Apart was recently restored by Kino—a remastered Blu-ray is available through them and is also accessible online via YouTube, Vudu, and AppleTV (you can also watch a free version of the non-restored film here). Subscribe to Sleeping All Day