Nowhere Man

Man Without a Map begins like so many other mysteries: a detective is hired by a woman to investigate the disappearance of her husband.

However, a dispassionate strangeness pervades the story, one that twists it away from the mystery genre and into a new realm entirely. The detective learns from the wife during their initial meeting that her husband in fact disappeared nearly six months ago, and she’s only now getting around to finding out what may have happened to him. Her brother, a creepy blackmailer type, keeps popping up around town while our detective makes his initial inquiries. Folks at the man’s job seem to remember he worked there once but have taken his sudden disappearance in such stride that his absence is no longer noticeable. Both the wife (Etsuko Ichihara) and her brother (Osamu Ôkawa), in pressing our detective for answers, seem more concerned in discovering the reason behind the man’s disappearance than in finding the man himself.

The wife (Etsuko Ichihara, left), and her scheming brother (Osamu Ôkawa, right)

Our detective (Shintarô Katsu) is not a lone-wolf workaholic who is his own boss; he’s an employee for a large unseen detective agency who has dispatched him onto the case. His initial enthusiasm is lukewarm at best (in our first view of him he’s distractedly picking his nose), and as the investigation proceeds and he encounters an increasing number of blank stares and blind alleys he starts to become just as apathetic as the woman who hired him. Although he’s tried to design a life in contrast to the mainstream—when asked why he became a detective, he answers, “It's the furthest thing from a normal job”—the detective starts to see parallels between the missing man’s life and his own. Both men are orphaned into a metropolis wholly indifferent to their aspirations or survival, working for an impersonal entity who judges his merit solely on results.

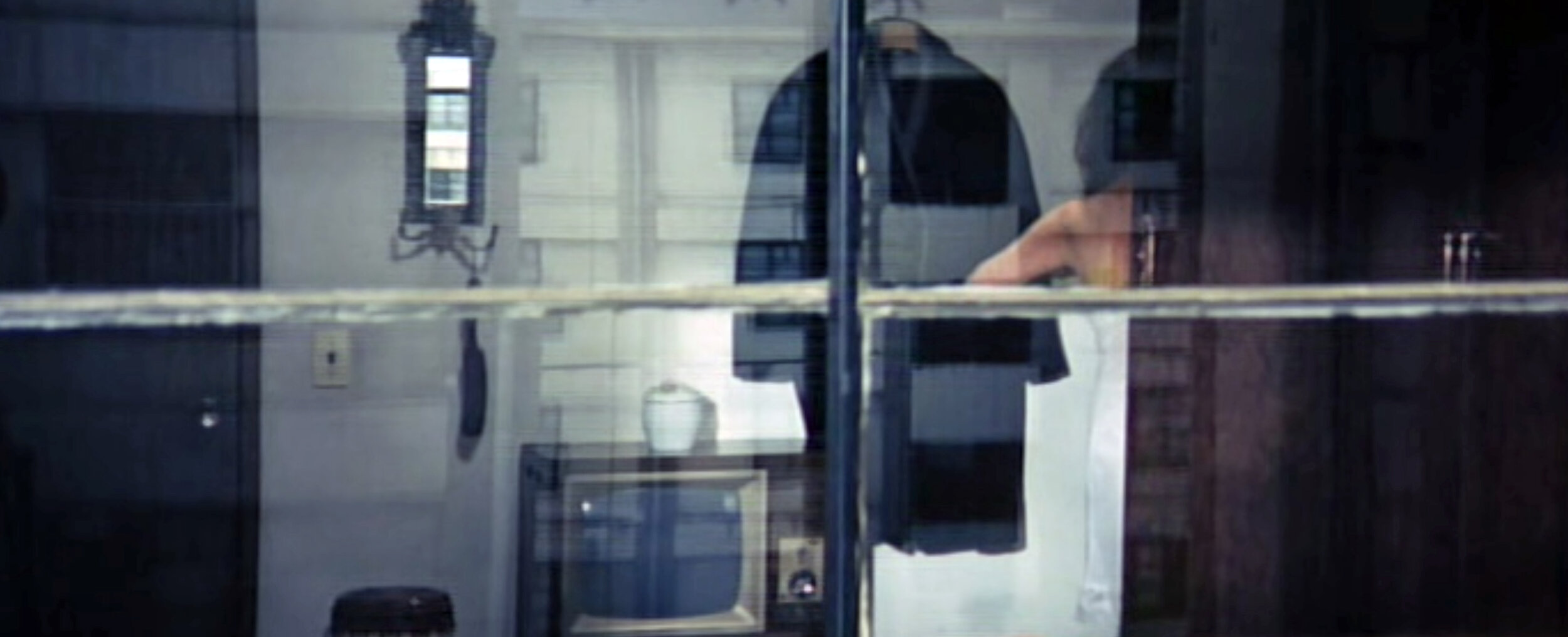

Our unnamed detective (Shintarô Katsu) in the midst of a hallucination

Man Without a Map was released in 1968 and was the fourth collaboration between author Kōbō Abe, director Hiroshi Teshigahara, and composer Tôru Takemitsu, after Pitfall (1962), Woman in the Dunes (1964), and The Face of Another (1966). Woman in the Dunes became an international arthouse smash, winning a Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and receiving Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Best Foreign Language Film. Man Without a Map is the only film of the four in color, and has a look and mood distinct from the other collaborations.

The film begins with a surreal sequence in bright, popping psychedelic colors, an amoebic kaleidoscope of sorts with various strains of music—rock, classical, radio static—fading in and out over the credits. These visuals dissolve into aerial cityscape views of Tokyo, with a woman’s voice describing “the little activities of a thousand souls.” Many shots are framed in a low-slung way that cuts off the heads and sides of the subjects speaking, or from odd angles though windows or doorways that give the impression that our detective is constantly being watched by someone unseen. As the detective’s search becomes increasingly fruitless the framing wanders farther and farther away from the action, at times no longer focusing on who’s speaking, as if even the film itself has become bored with the story.

Strange hallucinations begin to crowd in on our detective, daydreams that take him out of his pursuit and become inseparable with his reality. After he’s fired from the agency (impersonally, over the phone), and the nature of his relationship with the missing man’s wife becomes more intimate, the reality of the movie dissolves and the detective’s altered mindset becomes the dominant landscape of the film. In deciding whether to engage in a new narrative and begin a new life or withdraw from the scene entirely, he muses, “I will disappear too.”

The film’s aloof and deadpan attitude would make one want to associate it with other grim detective films of the subsequent decade like Hickey & Boggs (1972) and The Long Goodbye (1973). But Man Without a Map rejects any efforts to play upon the curdled nostalgia of Chandler-era gumshoes and instead achieves a wholly contemporary ennui that’s surreal and sincere. While the story may be purposefully dull its effect is compelling and revelatory. In playing upon our familiarity with the detective genre Abe and Teshigahara are prodding at our notions of existence, ambition, and legacy in a way that provides no answers but leaves a big, colorful mess in its wake.

Despite the wide availability of the other three collaborations of Teshigahara and Abe, Man Without a Map is sadly difficult to find and was not part of Criterion’s box set release. Versions can be gleaned online via fileshare services, and physical bootlegs are available for sale.