The Mark of Cain

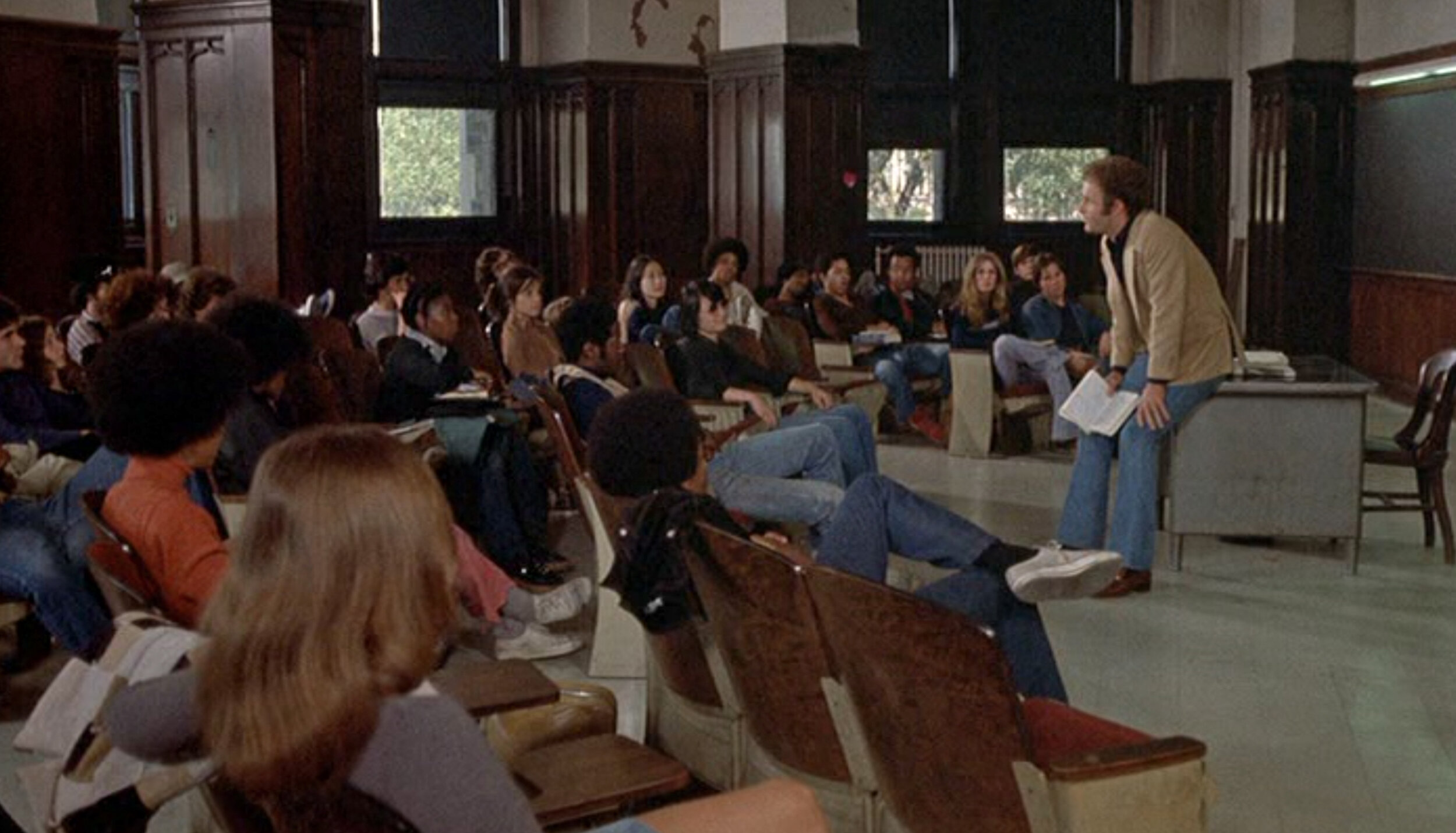

Axel Freed is living a charmed life. He has a chic girlfriend, a respected position as a literature professor, a mother who loves him. So of course Axel Freed is miserable. It’s too easy to go through life’s motions so effortlessly. He hungers for the edge—of danger, madness, whatever—the edge that he teaches about in his class, the one in Dostoevsky’s novels, a real dilemma that will test his character and force him to find out what kind of man he really is.

As The Gambler (1974) begins, Axel has gotten himself into a situation where he owes some tough people $44,000 after a night in a clandestine gambling house uptown. This isn’t the first time he’s lost money gambling, but this is the biggest hole he’s ever dug for himself. Axel (played by James Caan) only has a few days to come up with the money he owes, with the admission from his friend and protective bookie Hips (Paul Sorvino) that “the only thing standing between your skull and a baseball bat is my word.” Strangely, though, Axel doesn’t seem too phased about the insane amount of money he owes, and his loved ones are simply tired of this expensive “hobby” of his. When he mentions to his girlfriend Billie (Lauren Hutton) that he’s in the hole for so much she wryly snaps, “What is it this time, cock fighting?” His mother, Naomi (Jacqueline Brookes), is weary and beside herself when she learns the amount while Axel insists he’ll find a way to cover the loss, passively assessing how much she can give him toward the debt.

Left: Axel (Caan) with his mother Naomi (Brookes). Right: Billie (Hutton) is unfazed by her boyfriend’s escapades.

Amazingly, things start to work out. Even after he takes the piles of cash his mother withdraws for him and splits to Las Vegas for another spree rather than paying off Hips, Axel can’t seem to lose. He keeps hitting his number in roulette and all his blackjack hands add up to twenty-one. He now has plenty for Hips and then some. Rather than feeling elated or grinning like a man who’s cheated death, Axel becomes withdrawn. Sullen. It’s becoming too easy again.

His grandfather, A. R. Lowenthal (Morris Carnovsky), is a self-made man who worked his way up from a penniless immigrant into a furniture store scion. A. R. scraped and sweated his whole life, never knowing a day free from exhaustion and responsibility. Axel feels an inverse burden toward his grandfather, who raised him after his father died and Naomi was tasked with bringing up her son alone. Axel has never known the threat of true loss, depravation, or solitude; both mother and grandfather are intelligent enough to realize how serious Axel’s gambling issue is but too tied to their boy to refuse bailing him out time and again.

Left: Axel takes the cash. Right: With his grandfather A.R. (Carnovsky).

Axel denies Hips’s accusation that like most gambling addicts he’s addicted to losing, but he concedes, “I like the threat of losing.” Axel gambles not for the thrill, the win, or the loss, but for that queasy moment before anything, when he’s flying high without a parachute and the edge is closest to him. Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 haunts the film like a phantom, first appearing when Axel is cruising down the streets of Manhattan in his Mustang convertible after having lost the $44K, the creeping notes of the first movement mimicking the tense chill that Axel must feel while the roulette wheel is spinning, that sick feeling when the dealer is poised to throw down the last card. Mahler returns when he’s winning in Vegas, and again when he’s alone and empty, without the “juice” of a current bet running through his veins.

The Gambler was directed by Karel Reisz but we are thoroughly dwelling in screenwriter James Toback’s universe, whose heroes are often angsty streetwise intellectuals (see Sleeping All Day favorite Fingers [1978]) and the city is crawling with bookies, hoodlums, hustlers, and streetwalkers, played by New York–character-actor-favorites like Burt Young, Steven Keats, Antonio Fargas, and Allan Rich. Axel is a fine example of Toback’s archetypal hero, a man who is above his chosen lowlife environments yet beholden to them. He’s also out of place on his grandfather’s cushy and cultured estate, preferring his disheveled bachelor rattrap or his girlfriend’s hip but tiny walkup. In a scene in which his grandfather meets Billie, A.R. takes Axel aside and attempts to set him straight: “Get rid of her immediately. She’s not for you, she’s not the right kind of woman for a scholar, not the right kind of woman for a Jew.” The Gambler is a strange, messy film, but that’s why it’s so beguiling and interesting—in tapping this vein of “otherness” that sets Axel apart, the scene might provide another reason as to why he’s gambling, and then again it might not. Axel’s Jewishness is never brought up again, but it’s there. He’s better than his girlfriend’s polo-and-yacht set because he’s from heartier stock, a tougher and more ethnic background; yet he’s surviving on his grandfather’s money and living by teaching other men’s words. He’s never had to extract his rent from broken arms like Burt Young’s enforcer Carmine or endure hard labor like Dostoevsky. He’s never had to face danger and he’s determined to meet it, and soon.

The deeper Axel sinks and the more loved ones he sheds, the closer he is to enlightenment, with nothing between him and the uncaring world, nothing to save him from himself. In forcing a scenario where his blood is finally spilled, he dives into the stream of life. He is free.

A lovely restoration of The Gambler is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel. It is also available streaming via Amazon Prime, Hoopla, and Vudu. Subscribe to Sleeping All Day